- Date

- vendredi 29 décembre 2023

- Auteur

- Ryan Buhler, Forecast Program Supervisor

The 2023-24 season has started very dry with an unusually shallow snowpack. Many of the snow stations with historical snow data are showing near-record lows, some dating back a few decades. The main concern with a shallow snowpack is that weak layers are easier to trigger for a longer time, and they often become even weaker over time.

There are two layers currently at play: a layer of surface hoar buried at the start of December, and basal facets. These two weak layers recently caused several large avalanches in the Selkirks around Revelstoke and extending north into the Cariboo Mountains around Valemount. While most of the natural avalanches occurred Dec 23 – 25, sporadic avalanche activity continues.

This article primarily addresses the Columbia Mountains, but it's noteworthy that the Purcells and central Rockies, which are generally characterized by a thinner snowpack, have been reporting deep persistent slab problems for at least a couple of weeks now. This MIN post shows a recent example of a deep slab avalanche in the central Rockies.

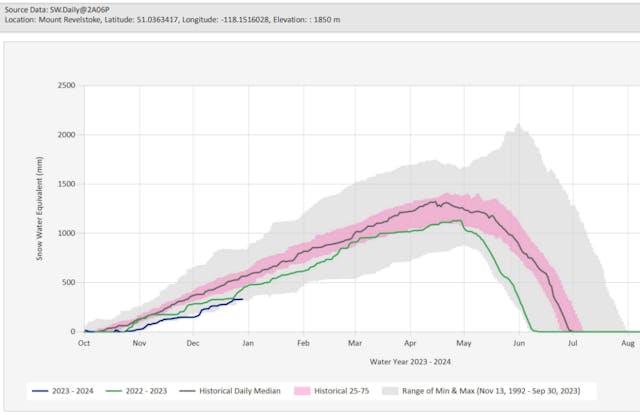

The snow pillow on Mount Revelstoke is showing near-record low snowpack, since 1992 (source)

A deeper dive into the shallow snowpack problems

Two deep avalanches are suspected to have been remotely triggered at 2100 m on a southwest aspect in the Monashee Mountains south of Blue River on Dec 23. (Photo: Willy Rens)

The persistent and deep persistent avalanche problems we’re seeing in these regions are primarily found in the alpine. While temperatures have generally been quite mild this season at lower elevations, it’s likely been cold enough to result in faceting snowpack gradients at higher elevations, especially in wind-exposed terrain where the snowpack remains thin.

The surface hoar layer exists at treeline and in the alpine and has been reactive for most of December in many of the interior regions (see this blog from Dec. 15 for more details). In the regions south of Revelstoke, a rain crust has made it more difficult to trigger this layer and has limited the amount of avalanche activity. Further north where that rain crust is thinner or doesn’t exist, recent milder temperatures appear to be causing the layer to gain strength at treeline elevations.

However, while it’s uncertain where and at what elevations this surface hoar layer continues to exist; professionals are still treating it with respect. Expect it to remain intact and reactive in some areas in the alpine.

Basal facets are the other concern in thin alpine snowpacks. While temperatures have not been unusually cold like last year, the combination of a very shallow snowpack with seasonal alpine temperatures has likely been enough to result in a faceting temperature gradient. As a result, layers near the base of the snowpack may be getting progressively weaker. For more details on snowpack faceting and temperature gradients, check out this blog from last year.

An estimate on locations where the two deep weak layers may be reactive.

Terrain management

Whenever problems like this start to develop, I immediately look to the guiding community and see how they are managing their terrain use. In addition to conservative terrain selection, they are also:

- Sticking to low-angle slopes and avoiding large, smooth, and steep features, especially in the alpine.

- Avoiding recently wind-loaded terrain features.

- Minimizing overhead exposure.

- Riding smaller slopes at treeline and below, where a bridging rain crust is known to exist.

Looking forward

While natural avalanche activity in the interior ranges has tapered off in recent days, there remains a lot of uncertainty about what the future holds for these weak layers. Relatively dry conditions are expected to persist for at least another week. These are ideal conditions for snowpack faceting to continue, especially where it’s thin at higher elevations. This means the basal faceting could get worse before it gets better.

The major tipping point for another substantial round of natural activity on the deep layers will likely be the next big storm. However, the long-range weather forecast remains relatively dry for at least the next week in the interior. By the time we get the next big storm, it’s possible that the surface hoar problem may have improved, and the basal facet problem may have worsened. We will continue to monitor both layers, so keep an eye on the bulletins for ongoing information on these problems.

Some examples of recent large, deep avalanches in the Columbia Mountains:

In the Selkirks east of Revelstoke on Dec 24, a large natural avalanche on solar aspect scrubbed down to rocks, and numerous other smaller releases in the same terrain. (Photo: Andrew McNab)

This avalanche at 2300 m on a northeast aspect likely initiated on the early-Dec surface hoar and scrubbed a small pocket down to the basal facets in the Selkirk Mountains east of Revelstoke on Dec 23. (Photo: Sean Cochrane)

A human-triggered avalanche at 2300 m on an east aspect failed on basal facets in the Selkirk Mountains northwest of Golden on Dec 25.

Wind loading is the expected cause of this natural avalanche at 2200 m on an east aspect in the Selkirk Mountains northwest of Golden on Dec 23. The avalanche failed on the early December surface hoar and stepped down or scrubbed down to the ground in many places.

A MIN report from the Selkirk Mountains north of Revelstoke on Dec 27: multiple natural avalanches were observed on south and east-facing aspects. All were on steep rocky peaks and ridges that let go of the whole slab/layer to rock. (MIN Report and Photo: HIGHPERFORMANCEINDUSTRIES)