- Date

- Friday, January 28, 2022

- Author

- Tyson Rettie, Avalanche Forecaster

It’s here to stay…

The early December crust/facet persistent weak layer (PWL) is now a well-established feature of this season’s snowpack. The atmospheric river events that created this layer were unprecedented, in terms of their intensity. But the resulting layer is not. We’ve seen these “rain on snow” events before, and those experiences provide us insight into how things might play out in the coming weeks and months.

The winter of 1996 – 97 had many similarities to this season. In early November, a rain on snow event occurred from the Coast Ranges all the way east to the Rocky Mountains. On Nov 11, that wet layer was buried by dry snow. Then an Arctic air mass took hold and froze the moist Nov 11 layer, resulting in a widespread crust under the dry snow.

This combination of moisture and cold temperatures produced a layer of facets on the crust, which resulted in a PWL that produced large, destructive avalanches throughout the winter and into the spring. The 96 – 97 mid-November crust/facet PWL proved to be deadly and was linked to seven of the 13 avalanche fatalities that occurred that year.

- Credit

- Raven Eye Photo

Avalanche Canada avalanche technician Ben Hawkins holds up a 3 cm thick crust found with overlying facets in his snowpit (file photo).

If you want to dive into the science of rain on snow events and crust/facet PWLs read this article by Dr. Bruce Jamieson: The Facet Layer of 1996 in Western Canada. Crust/facet layers are very diverse in how they form, how they bond to layers above and below, and how they evolve over the season. Generally, strength and bonding fluctuate, giving us periods where they are reactive interspersed with dormant periods when they are largely unreactive. While it’s hard to say definitively how this season’s crust/fact PWL will play out, the AvCan forecasting team is increasingly thinking this layer will remain a problem in the Monashees, Selkirks, Purcells, and parts of the Rockies for the remainder of the season.

This layer is known to exist in parts of the South Coast ranges and it’s possible that it will come out of dormancy there later in the season. And it’s possible we’ll see it come to life in other places where it’s not yet been a significant problem.

We’re now in what’s called a low-probability/high-consequence scenario, which means avalanches on this layer are not easy to trigger, but those that do occur are often massive, even historical. Like the one that occurred on January 22 in the Jack Macdonald avalanche path east of Revelstoke near the western boundary of Glacier National Park.

- Credit

- Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure

Debris from a size 4.5 avalanche covers the avalanche shed at the Jack Macdonald avalanche path in Glacier National Park.

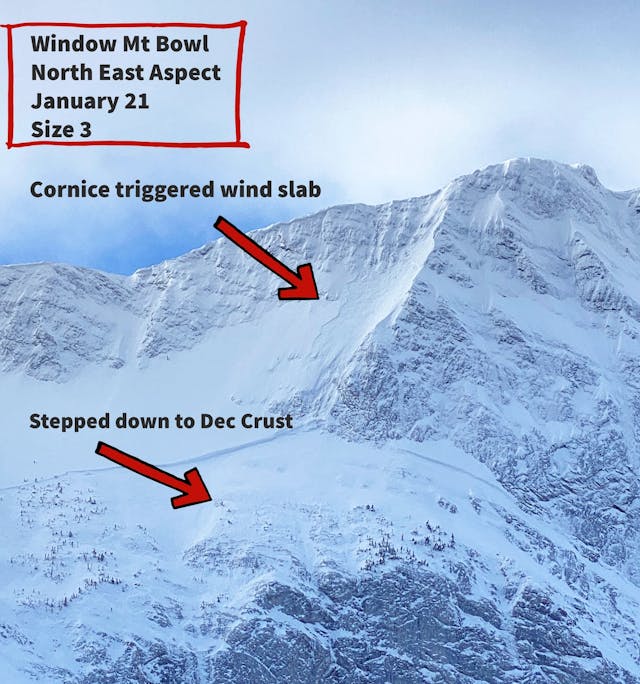

Natural triggering in this situation often involves things like cornice falls or step-down avalanches, where a slide initiates higher in the snowpack, then overloads and triggers the deeper PWL. Human triggering most often occurs in shallow snowpack areas or where the snowpack depth varies significantly across a slope. For both human and natural triggers, the likelihood of avalanches involving a PWL is higher when the weather changes.

- Credit

- Avalanche Canada South Rockies

The early December PWL is here to stay in many parts of western Canada. There may be periods of time without large avalanches but that doesn’t mean it’s gone. Here are some things you can do to reduce risk for the rest of the season where this layer is a concern:

- Avoid large start zones.

- Avoid slopes with cornices above.

- Stay away from shallow snowpack areas.

- Stay away from variable depth snowpacks where thick to thin areas exist.

- Reduce exposure to tracks and runouts of large avalanche paths, right down to valley bottom.

- Avoid terrain traps.

- Eliminate exposure to avalanche terrain at the onset and during weather changes, and keep it dialed back for a few days after. Weather factors that sensitize PWLs include:

- New snow or wind loading, especially rapid loading.

- Rain.

- Temperature changes, especially rapid changes from cold to warm.

- Strong solar radiation, especially a sudden onset such as early morning on sun-facing alpine start zones, or when clouds open and the sun pops out during the day.

Every season is different. Last season was filled with epic stories of first descents in aggressive terrain, but these kinds of activities carry more risk this year. This year is all about the long game. It takes patience and discipline to keep these long-term problems in mind every day, and ongoing vigilance to recognize when and where the layer is likely to be more sensitive to triggering.

Avalanche Canada forecaster, Zoe Ryan, conducts a recent propagation test in the Corbins area near Glacier National Park. See the full video with sound.

By Tyson Rettie, Avalanche Forecaster, and Karl Klassen, Warning Service Manager